Women’s History Month series

Links to interviews (and transcripts) with Melbourne women who protested against the Vietnam War and the National Service Act.

(list continues below)

Continue reading →Long Live Evil: Sarah Rees Brennan

I read this courtesy of NetGalley. It’s out at the end of July.

This book is for everyone who ever day-dreamed self-insert-fic, and didn’t really think through the consequences. (How distracting would I really have been to Biggles and Algie and Ginger? I don’t care about Bertie.) It’s also for those people who connect with the line “always rooting for the anti-hero” (omg turns out I like a Taylor Swift song??).

This book is amazing and wonderful and didn’t do what I expected except insofar as I was, indeed, constantly surprised by events and personalities. Surprised and delighted and absorbed and, not going to lie, a bit stressed out.

At 20, Rae is dying from cancer. Her sister keeps sharing their favourite books with her, to keep her company and to have some joy in her life. Rae didn’t pay much attention to the first book, but then things got interesting in the second. Why does that matter? Because when Rae finds herself in the world of those books, early in the timeline of the first book – in the body of a significant character – trying to figure out what’s going on, and how to fit herself in, is going to be crucial. And, well. As you can probably expect, it doesn’t entirely go to plan. Oops?

Brennan is doing A LOT here. Rae’s experience with cancer – the disease and other people’s reactions, and everything else lost because of it – reads very, very real (turns out Brennan has had very serious cancer recently; I am highly averse to reading authorial experience into books, but sometimes it’s real). So there’s that. And when Rae wakes up in her new body, she needs to figure out what she’s meant to know (and not know), and how she’s meant to act. The decision to embrace the (supposed) villainy of the character she’s inhabiting is a fascinating one with all sorts of consequences, and allows Brennan to comment on all of those Villain Tropes – and especially Lady Villain Tropes – that authors and films have loved to rely on. My particular favourites are the critiques about gravity and balance if you’ve got the boobs of the Classic Evil Seductress.

Sure, it’s got a character dying of cancer, and the fictional world she spends most of her time in is actually not a very pleasant place at all with deeply problematic characters and a dreadful social structure; people die needlessly, and the class structure is appalling. However, it’s Sarah Rees Brennan: this book is also FUN. It’s fast-paced, it loves life, it gets into tricky situations and tries to talk its way out of them, it has people trying to introduce house music where it really doesn’t belong. I consumed this novel and now I’m pining for the sequel and I don’t even know when it will be released.

Highly, highly recommended.

Embroidered Worlds anthology

I read this courtesy of NetGalley and Atthis Arts; it’s out now.

“Fantastic Fiction from Ukraine and the Diaspora”: what a brilliant anthology.

The only theme uniting this anthology is that the authors are from Ukraine, or part of its diaspora. That means that there’s a huge range of types of stories: those that are clearly rooted in folklore (even if I wasn’t familiar with the original); those that are ‘classically’ science fiction; some that are slipstream, some that slide into horror, and a few where the fantastical aspect was very subtle. Some of the stories are very much ABOUT Ukraine, as it is now and as it has been and how it might be; other stories, as you would expect, are not.

One of my favourite stories is “Big Nose and the Faun,” by Mykhailo Nazarenko, because I’m a total sucker for retellings of Roman history (Big Nose is the poet Ovid; it starts from the moment (based on the story in Plutarch, I think) of the death of Pan and just… well. The story does wonderful things with poetry and “civilisation” and nature, and I loved it.

I loved a lot of other stories here, too. There was only one story that I ended up skipping – which is pretty good for me, with such a long anthology – and that was because it was written in a style that I basically never enjoy (kind of Waiting for Godot, ish). RM Lemberg’s “Geddarien” was magic and intense and heartbreaking – set during the Holocaust, cities will sometimes dance, and for that they need musicians. Olha Brylova’s “Iron Goddess of Compassion” is set a few years in the future, and the gradual revelation of who the characters are and why they’re doing what they’re doing is some brilliant storytelling. “The Last of the Beads” by Halyna Lipatova is a story of revenge and desperation, with moments of heartbreak and others that I can only describe as “grim fascination”.

I’m enormously impressed by Attis Arts for the effort that’s gone into this – many of the stories are translated, which brings with it its own considerations and difficulties. This book is absolutely worth picking up. If you’re interested in fantasy and science fiction anthologies, this is one that you really need to read.

Ela! Ela! review

This book was sent to me at no cost by the publisher, Murdoch Books. It’s out now, RRP $39.99.

There are some excellent aspects to this cookbook, and there are some that I am not wild about.

The good: I adore a cookbook that is also part-memoir. Mittas is from Melbourne. She spent some time living and working in Turkey and Crete; each chapter of the book is about one of the places she lives – two in Turkey, then Crete, and then a section at home. Chapters start with a short narrative about Mittas’ experiences in those places, which seem to have largely been quite difficult – partly as a result of language barriers, and partly because often, what Mattis wanted wasn’t what the people she was working for could offer. These were intriguing insights, but they are more (to use a culinary metaphor) bite-sized chunks than anything like a meal.

The recipes fall into both good and not-wild-about categories. The ones I tried were mostly good! But I had some issues with the way they’re written.

- Slow-cooked lamb shoulder: very tasty; serving with tahini yoghurt, sumac onion, and yoghurt flatbread was excellent.

- Spanakopita: an excuse to make this at last! Excellent! Except… the rest of the title is “with Homemade Filo” – and, just, no. She does at least suggest using a pasta machine to roll it out – I have one, but many don’t. Why would you not have a “And if you can’t be bothered, this will use XX sheets of store-bought pastry”? Which is what I did and just made it up. The recipe also calls for “1/2 bunch silverbeet” which is… how much exactly??

- Gigantes with tomato and dill: fine. Tomato and dill is a combo I didn’t know I needed!

- Stuffed capsicum: again, fine, but some issues with the writing. It calls for 6 capsicums but says it serves 5 – ?? It also says to cover the capsicum with baking paper and foil, but that you should add more stock if required: how does one check on that?

- Galaktoboureko: not going to lie, having the excuse to finally make this Monarch Of All Desserts was worth getting the book. Kind of a cross between vanilla slice and baklava, it’s a truly glorious thing, and the recipe was fine.

So. Not my favourite cookbook of all time, but fine. Not one I’d recommend to a complete novice – there are definitely bits where there is assumed knowledge about how cooking works – but if you’re looking for an Australian-written, fairly eclectic take on Turkish and Greek food, this would work.

A Sorceress Comes to Call

Read via NetGalley. It’s out in August (sorry).

My experience of reading this went like this:

– Got the email that I was approved to read this.

– Thought, “oh, I’ll just download that so it’s ready to read.”

– Thought, “oh, I’ll just start it to see what it’s like.”

– A few hours later, thought, “oh. Now I’ve finished it and I no longer have a Kingfisher novel to look forward to.”

So that’s my tragedy. Of course, I DID get to read it in the first place, so it’s not MUCH of a tragedy.

This book is, unsurprisingly, fantastic. I adore Kingfisher’s work and this is another exemplar. Cordelia’s mother is able to literally control her body – she calls it ‘obedience’ – and as a result, even when she is in control of herself, Cordelia is always on her best behaviour. She has no other family, and no friends except for Falada, the horse, and the passing acquaintance of a neighbouring girl. She has no control over anything – doors are never to be closed in their house – and all she expects of the future is that she will marry a rich husband: so her mother has told her.

Things begin to change when her mother’s current ‘benefactor’ decides to stop seeing her, and providing for her. In order to remain in the style to which she is accustomed, Cordelia’s mother decides to find herself a rich husband, both so that she herself will be looked after and to aid in the effort to marry off Cordelia. This brings the pair into the orbit of Hester and her brother, a rich squire. Through the mother’s machinations, they come to stay at the squire’s house, and Cordelia’s mother sets about wooing the squire. Meanwhile, Hester gets to know Cordelia, and… well. As you might expect, there are ups and downs and revelations and terrible things happen and, eventually, most things turn out okay.

The writing is fast-paced and glorious. The characters are utterly believable. Apparently this is a spin on “The Goose Girl” but it’s not a tale I know very well, so I can’t tell you where Kingfisher is being particularly clever in that respect. But it makes no difference; this is a fabulous novel and Kingfisher just keeps bringing the awesome.

Lady Eve’s Last Con, Rebecca Fraimow

Read via NetGalley. It’s out in June 2024.

I was convinced that this must have been a second in a series – even when I was a third of the way through – but it turns out that the author has just set up a truly impressive amount of backstory for this one to happen. I mean, I know most good stories have their backstory, but this one REALLY felt like I was being given the “in case you don’t remember what happened in the last book” spiel.

Ruth is a con artist. Her latest con is playing Evelyn Ojukwu, shy and slightly naive debutant, with the aim of catching the eye – and hopefully a promise of marriage – from the incredibly wealthy Esteban. But she has no intention of marrying him: instead, it’s all about the money… and here’s where the backstory comes in: because Esteban done Ruth’s sister wrong, and this is a revenge game. The fact that Esteban has an awfully attractive, Don Juan-esque, half-sister is a complicating factor that Ruth hadn’t expected.

The book is set an unspecified long time in the future; humanity has spread to many different planets and systems (it took me until maybe halfway through to realise that this book was actually set on a satellite of Pluto). The details of how all of that side works are fuzzy and irrelevant. The distances involved, though, are a significant factor – there’s no super-fast communication between planets, for instance, and the lag is a critical one for both personal and business reasons, which Fraimow uses well.

I am amused by the idea that partner-catching would still be as much of a big deal in this sort of society as it’s portrayed to be in Regency England, and that the class issues are just as real. Because that’s basically what this is – it’s a Regency-like romance, with space travel and artificial gravity. It’s fluffy (that’s a positive term!) and light-hearted, with the nods to substance that show the author is quite well aware of what they’re doing, thank you very much. If you need something enjoyable, with a bit of tension and drama but the comforting knowledge that things will turn out ok, even if it’s not clear how, this book is what you need.

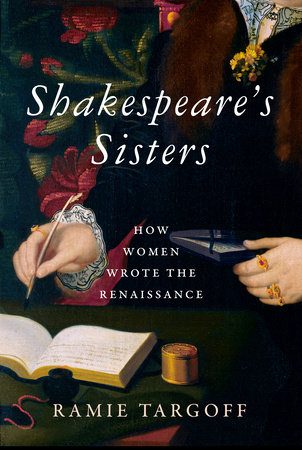

Shakespeare’s Sisters, Ramie Targoff

Read via NetGalley. It’s out now.

I’m here for pretty much any book that helps to prove Joanna Russ’ point that women have always written, and that society (men) have always tried to squash the memory of those women so that women don’t have a tradition to hold to. (See How to Suppress Women’s Writing.)

Mary Sidney, Aemilia Lanyer, Elizabeth Cary and Anne Clifford all overlapped for several decades in the late Elizabethan/ early Jacobean period in England – which, yes, means they also overlapped with Shakespeare. Hence the title, referencing Virginia Woolf’s warning that an imaginary sister of William’s, with equal talent, would have gone mad because she would not have been allowed to write. Targoff doesn’t claim it was always easy for these women to write – especially for Lanyer, the only non-aristocrat. What she does show, though, is the sheer determination of these women TO write. And they were often writing what would be classified as feminist work, too: biblical stories from a woman’s perspective, for instance. And they were also often getting themselves published – also a feminist, revolutionary move. A woman in public?? Horror!

Essentially this book is a short biography of each of the women, gneerally focusing on their education and then their writing – what they wrote, speculating on why they wrote, and how they managed to do so (finding the time, basically). There’s also an exploration of what happened to their work: some of it was published during their respective lifetimes; some of it was misattributed (another note connecting this to Russ: Mary Sidney’s work, in particular, was often attributed to her brother instead. Which is exactly one of the moves that Russ identifies in the suppression game). Some of it was lost and only came to light in the 20th century, or was only acknowledged as worthy then. Almost incidentally this is also a potted history of England in the time, because of who these women were – three of the four being aristocrats, one ending up the greatest heiress in England, and all having important family connections. You don’t need to know much about England in the period to understand what’s going on.

Targoff has written an excellent history here. There’s not TOO many names to keep track of; she has kept her sights firmly on the women as the centre of the narrative; she explains some otherwise confusing issues very neatly. Her style is a delight to read – very engaging and warm, she picks the interesting details to focus on, and basically I would not hesitate to pick up another book by her. This is an excellent introduction to four women whose work should play an important part in the history of English literature.

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

I received this book to review at no cost, from the publisher Hachette. It’s out now (trade paperback, $34.99).

As someone who has been keen on ancient history since forever, of course I was intrigued by a new book on the seven ancient wonders. And I’ve also read other work by Hughes, and enjoyed it, so that made me doubly intrigued.

Before I get into the book: of course there is controversy over this list. Hughes acknowledges that, and goes into quite a lot of detail about how the ‘canonical’ list came about – the first surviving mention of such a list, why lists were made, what other ‘wonders’ appeared on such lists in the ancient world of Greece and Rome, as well as what other monuments could be put on such a list were it made today. I appreciated this aspect a lot: it would have been easy to simply run with “the list everyone knows” (where ‘everyone’ is… you know), but she doesn’t. She puts it in context, and that’s an excellent thing.

In fact, context is the aspect of this book that I enjoyed the most. For each of the Wonders, Hughes discusses the geographical context – then and now; and the political, social, and religious contexts that enabled them to be made. This is pretty much what I was hoping for without realising it. And then she also talks about how people have reacted to, and riffed on, each of the Wonders since their construction, which is also a hugely important aspect of their continuing existence on the list.

- The Pyramids: the discussion of the exploration inside, by modern archaeologists, was particularly fascinating.

- The Hanging Gardens of Babylon: the discussion of whether they even existed, and if so where, and what ‘hanging’ actually meant, was intriguing.

- Temple of Artemis: I had no idea how big the structure was.

- Statue of Olympia: I had NO idea how big this allegedly was.

- Mausoleum of Halikarnassos: NOT HELLENIC! Did not know that.

- Colossus of Rhodes: also had no idea how big it allegedly was, nor the discussion around its placement.

The Practice, the Horizon, and the Chain

Read via NetGalley and the publisher, Tordotcom. It’s out in April 2024.

To be honest I don’t even know where to start with reviewing this novella.

To say that it’s breathtaking is insufficient. I can say that it should be on every single award ballot for this year, but that only tells you how much I admired it.

I could try and explain how it explores ideas of slavery, and the experience of the enslaved; ideas of control, and social hierarchy; about human resilience and human evil. Draw connections with Ursula K Le Guin’s “The Ones who Walk Away from Omelas,” and probably a slew of stories that connect to the Atlantic slave trade and which I haven’t read (mostly because I’m Australian).

There are odes to be written to the lyricism of Samatar’s prose, but I don’t myself have the words to express that. Entire creative writing classes would benefit from reading this, and sitting with it, and gently prying at why it works the way it does.

I could give you an outline? There’s a fleet of space ships, and they’re mining asteroids, and mining is dreadful work so you know who you get to do the dreadful work? People that you don’t call enslaved but who are indeed enslaved. There’s an entire hierarchy around who’s doing the mining in the hold, and who’s a guard and who’s not a guard, and the people at the top have convinced themselves there’s not REALLY a hierarchy it’s just the way things need to be. Sometimes someone from the Hold is brought out of the Hold, and then has to learn how to be outside of the Hold… and then someone starts to see through the system, and maybe has a way to change things.

The outline doesn’t convey how powerful the story is.

I should add: the main characters are never named.

Just… everyone should read this. It’s not long, so there’s no excuse! But it will stay in your head, and it will punch you in the guts. In the good way.

These Fragile Graces, This Fugitive Heart

Read via NetGalley and the publisher, Tachyon. Out in March 2024.

A completely believable, dystopic Kansas City where the police and everything else are basically run by corporations and only for the rich (cue an Australian rant about modern USA, if you please).

An anarchic commune that’s attempting to be a place where people feel safe, and are allowed to be what and who they want – and which really gets up the nose some rich people.

A trans woman, Dora, who used to live in said commune, and left over differences of opinion about security, and has been making her way for the last few years as a security consultant.

And Dora’s ex-girlfriend, still living in the commune, who is found dead – allegedly of an overdose, but Dora discovers evidence of foul play.

This is a fast-paced thriller novella (novelette? not sure) that I devoured very quickly. Dora is complex, driven, committed, sometimes bitter, and absolutely determined to get answers, even when that might hurt herself or other people. The setting is believable and horrifying, drawn with broad strokes but enough detail that you can see Wasserstein has put a lot of thought into it; and it makes me wonder what modern KC-dwellers think of it, and if they can see the places she describes. It works as a thriller – there are twists and reveals – and just overall it’s very clever. Hugely enjoyable, and I look forward to seeing what else Wasserstein has up her sleeve.

Bespoke and Bespelled

I read this courtesy of NetGalley. It’s out now.

Marnie is:

- a New Zealander,

- living in LA, because she is

- working as a costume supervisor, and

- a stitch-witch: fabric loves her and wants to make her happy.

She is also: - 41,

- ‘generously proportioned’,

- currently single, and

- bi (or pan? unclear).

As the story opens, the show she’s working on has finished, and Marnie is hoping for a position not just as a costume supervisor, but as a designer. And so when a position comes up back home, adapting one of her favourite fantasy series for the big screen, she agrees.

Note: the little nods to what LOTR did for NZ are a delight.

Basically the story is about Marnie on the film set, dealing with a) her attracting to the leading man, and b) weird occurrences that have plagued the filming since it started in NZ, and which begin to seem like they’re not random or natural.

Coming to Healey off the back of the Olympus Inc books, this is exactly what I was hoping for. Cosy, comfortable, fast-paced: I read it in one evening and I have no regrets.